Adventures in the Trade

Granite Guys No More

(All photos by Jason Nottestad)h

By Jason Nottestad

There was a time, not too long ago, when a busy shop meant lots of natural stone being processed. Ten years ago, the shop I worked at thrived on the basic colors of quartz and granite. Fast forward through the monolith that was white quartz with marble patterns, we come out on the other side with a much more varied offering. For the customer, this means a world of color and texture possibilities. For the fabricator, this means another learning curve in a career full of them. In my current shop, a busy day for us may or may not include granite. Quartz remains a staple, but porcelain, glass, and marble can also fill the day. While quartz fabrication has been perfected for over a decade and marble is difficult but well-tested, learning to work with porcelain and glass has challenges in both material and application. Sometimes the challenges happen before the material even gets to the machines. My current shop purchased a container of porcelain from Italy, and it arrived during the period our building was being renovated. Our biggest forklift was large enough to easily handle the frame with 20 slabs of 12mm porcelain on it, but it was stuck in another part of the building, and internal passages hadn’t yet been enlarged for the vehicle. Our first porcelain unload became a nerve-wracking exercise in extracting and moving around A-frames with an another, undersized forklift. To make matters worse, the level of the dock was lower than the level of the container bed. We improvised by using a rubber tire chock to cushion the drop from the container to the building level. I’ve never been more happy to see an empty container!

Fabricating a straight edge on porcelain can be tricky, but it's a new level with a constant curve.

A light material doesn’t necessarily like to stay in a stationary position on the saw table.

Sometimes the challenges can be small but irritating. When we received our first 12mm porcelain project, we discovered our lifting clamp wouldn’t close-up enough to pick up a slab. Improvising for a second time, we used a 2cm quartz spacer to move the slabs around until the thinner porcelain clamp arrived. We also tested the theory that 12mm porcelain slabs are not that heavy. We were able to move them around with lifting handles without too much strain. Fabricating thin porcelain slabs presented some challenges as well. A light material doesn’t necessarily like to stay in a stationary position on the saw table, and can even seemingly ‘float’ a little from the water being applied to the blade. We had some issues with piece movement in the beginning, but the learning curve was short and we successfully cut porcelain quickly. Adapting to the material application itself was a longer learning curve. For fabricators accustomed to working mainly with horizontal applications, the switch to large scale vertical applications like shower panels presented the need for a true change of mindset. The regular countertop problems of fitting a piece around a corner or bumping into a wall cabinet with an ‘L’ piece are suddenly very minor.

Porcelain installations need plenty of planning ... and a little levitation now and then.

An installer quickly learns that installing 12mm vertical panels is real work – perhaps more difficult than installing countertops.

Going vertical involves a new set of installation skills.

For a countertop guy, the only vertical applications you see on a regular basis are full height backsplashes. While full-height splash can be a challenge, at 18” high it’s generally a manageable one. Moving to pieces that are 48” X 96” with an 1/8” clearance at the top and bottom means having to think through and plan every phase of the installation process. The entire jobsite becomes an obstacle course, and every item in the room you’re installing is an impediment. We began to ask ourselves all sorts of questions about the jobsite during the template. The main question: Does the location allow your installers enough space to bring a panel from the horizontal carrying position into the vertical application position? We’ve dealt with both locations where it was possible and where it was impossible and need a field seam to be added. Even where it was possible, the panel needed to be angled back toward the installers to stand it upright and lift it over the edge of the shower pan. An installer quickly learns that installing 12mm vertical panels is real work – perhaps more difficult than installing countertops. Jobsite obstacles can get in your way when installing porcelain as well. We recently set a wall-to-wall tub deck where the tub is suspended over the top of the tub area. Because of that wall-to-wall deck, we had to stand the piece nearly vertically on top of the deck in order to get the piece set … and that’s impossible with the tub in the way. Because the tub would no longer fit out the door, we were forced to slide the tub on 2 X 4s into the middle of the room, still suspended above our heads, in order to make room for the tub deck to be installed. Precarious, but successful.

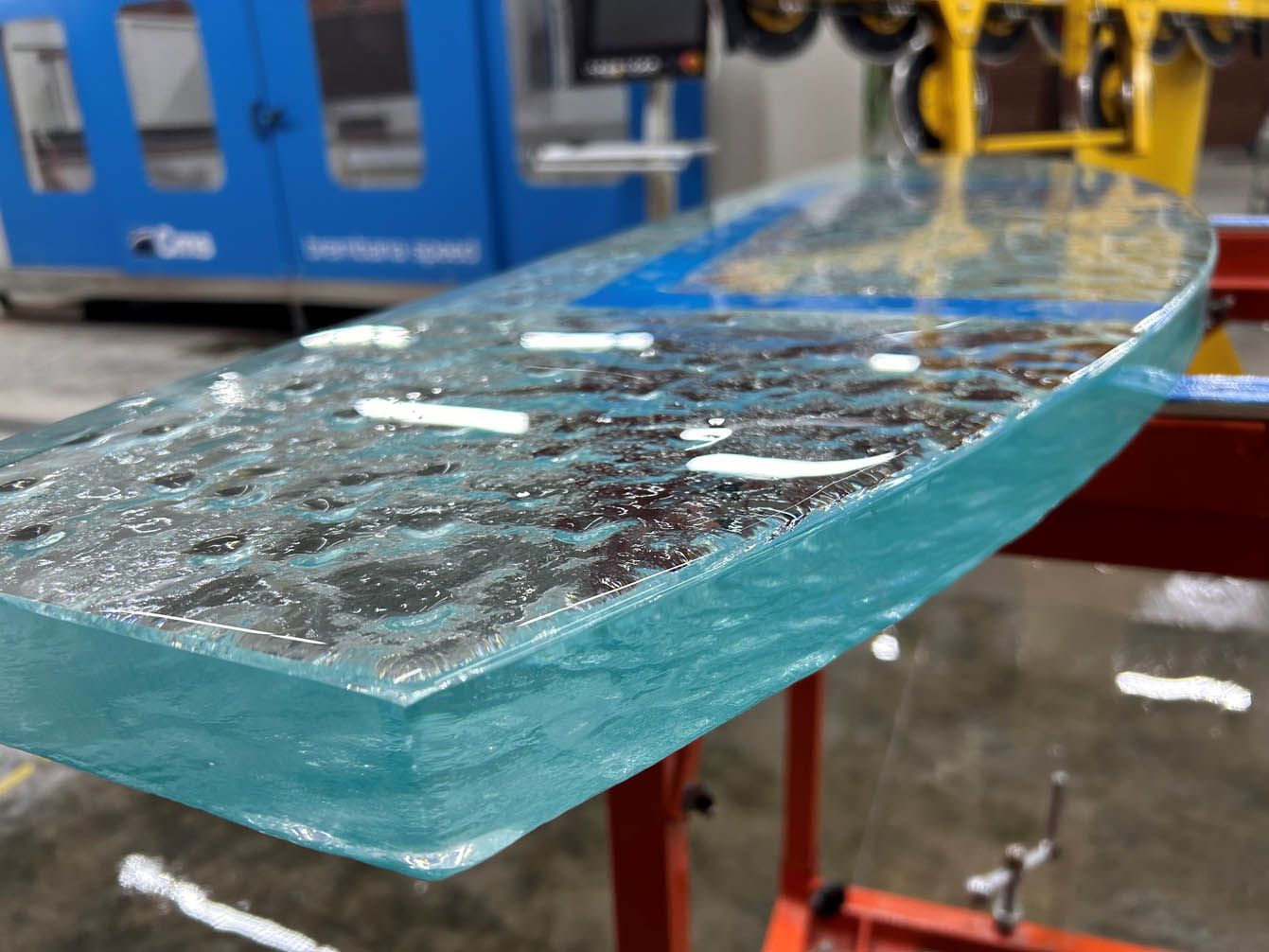

Because of the uneven surface of kilned glass, profile tooling is also out the window.

Installing vertical applications also means an investment in a new set of tools a typical countertop installer isn’t going to have. A full set of tile tools -- notched trowels, leveling shims, a mortar vibrator, and an upgraded set of suctions cups -- are going to be needed. In addition, you’ll need another upgrade to a porcelain grinder blade for on-site adaptions to be chip-free. That all-purpose granite blade will chew up a porcelain edge. For glass, the challenges are equally about fabrication and installation. On the fabrication side, the heft of the product can create problems. A fabricator is lucky if the glass is 3cm-thick and can be cut and milled with existing tooling. Many glass countertops are 2” thick and can run up to 5”. Specialized tooling is required as material goes beyond standard countertop thicknesses, as blades with a too-small diameter become unusable. Core and fingers bits also need to be long enough to accommodate the extra thickness of glass. Because of the uneven surface of kilned glass, profile tooling is also out the window. Quality handwork skills are a must for polishing the edges of glass tops. On the installation side, glass painted on the bottom side needs to be set with a great deal of care to avoid scratching. For the countertop guy accustomed to sliding tops into place, this is a new mindset for sure. While granite and quartz retain the top spots in the hard-surface spectrum, a shop that expands its ability to offer alternate hard surfaces is looking toward the future. Overcoming learning curves on new materials is well worth it, however, when new opportunities follow and your shop stays busy.

Glass tops bring another set of challenges with fabrication and installation.