Are Edges Still an Edge?

New materials, customer trends cutting into profile choices

Previous page: Cosentino | Above: ©2024 Cutting Edge Countertops

By K. Schipper

Not so long ago, a key component of nailing the sale on countertops was the edge options a shop could offer. Those edges, often hand-crafted, included six or seven of top profiles, typically offered an upsell on the job. A simple profile might be included in the price just to keep the work flowing. Today, a lot has changed. Along with natural stone, today’s shops are fabricating quartz and possibly sintered materials, and the handwork has often been replaced with a line polisher and a router. Styles – or if you prefer, fashion – changed, too. Many buyers today are looking for an eased edge or mitered one – but customers unsure on choices are happy to take advice on what they’re buying.

“We do most eased edges, a little bit of mitered, and then a random edge thrown in there about once a week.”

Camden Creek Countertops of Memphis Memphis, Tenn.

Changing Fashions

So how many different edge profiles does your shop do in a week? If the number is low, you’re not alone. “In a week the majority are eased-edge profiles,” says Camden Creek, production manager at Memphis, Tenn.-based Countertops of Memphis. “I don’t consider a mitered edge to be an eased one, so three if you count mitered. We do most eased edges, a little bit of mitered, and then a random edge thrown in there about once a week.” In Great Falls, Mont., Tony Malisanti of Malisanti Inc., says his typical week also sees on average no more than two or three different edges, as well. However, that number grows to four or five different edges per week for El Paso, Texas-based 77 Stone, according to owner Edward Le Puma. On the other hand, Michael Bratti, president of R. Bratti Associates in Alexandria, Va., says about all the company’s jobs have specialized profiles. The company has done work for such Washington-area icons as the original installation of the Kennedy Center, the Hart Senate Office Building and the National Air and Space Museum. While the number of edges customers want may have changed along with the equipment and materials, one thing that still hasn’t changed is that customers often need help in choosing an edge for a particular job. “It seems like those who specifically want an ogee or an edge like that are the ones who know,” says Malisanti. “They’re also open to paying extra for it. They’re the people who have done their research, or they may already have had stone or quartz countertops, so they understand the concept of putting an edge on.” He adds that most people buying quartz these days ask for an eased edge, something he refuses to do on natural stone because of maintenance issues. There he recommends some type of radius edge. Le Puma says even those who are countertop novices care about getting the right edge, “they’re just not sure exactly what they’re caring about yet.” He adds that he thinks some of what people are seeking is a matter of regional desire. “It also depends on the types of homes,” Le Puma says. “Most people nowadays are going with clean, simple lines, and that means eased edges and mitered edges.” Creek agrees. “That’s what a lot of people are seeing in the design magazines,” he says. “It’s easy for us to sell because our salespeople tell customers this is what everybody likes, it’s clean and it’s modern. We also don’t charge extra for it, and it’s so easy; it’s the fastest thing to go through the shop.”

“Most people nowadays are going with clean, simple lines, and that means eased edges and mitered edges.”

Edward Le Puma 77 Stone El Paso, Texas

“Most everything we do is done by hand for quality control, or assembled from a router with multiple pieces”

Michael Bratti R. Bratti Associates Alexandria, Va.

A Matter of Tooling

What makes eased and mitered edges easy for shops to sell and fabricate is that the idea of the handcrafted edge rode out of town in a two-wheel drive pickup. “We’ve got a router that will do all the edges we offer except, I think, beveled,” says Creek. “We’ve also got an inline polisher, so in a perfect world of production, when pieces come off the router they’re done, and they don’t need to be touched up at all. With some of the eased edges, we’ll do about half on the inline polisher, and those will be touched up just to keep the hand fabrication guys busy.” Malisanti estimates anywhere from 90% to 95% of his edges are done on the router. “We still have some funky edges that we don’t have cutters for from the old days,” he says. “However, the ability to do it with a (CNC) router makes it a simpler process.” Le Puma says the only edge his shop will do by hand is a rope edge. On the other hand, Bratti says his shop will do edges both ways. “Most everything we do is done by hand for quality control, or assembled from a router with multiple pieces,” Bratti says. The move away from handcrafted edges is such that Malisanti says he’s willing to go out of his way to tool up for special jobs. For instance, the company did a piece that was supposed to look like a cornerstone on an old building. “We had a manufacturer make the edging tools,” he says. “If we have something like that, we’ll have them custom-build both tooling that can be used on the big machine and then tooling that can be used on some type of hand machine like a router. That way, if we run into a breakdown during the job, we’re not in a tough situation.” Tooling has had the greatest impact on mitered edges. While some buyers go for eased edges, or even a small bevel, the fact that a mitered edge looks cool and crisp has taken it way beyond its initial uses for waterfalls and porcelain. “In the beginning, when porcelain and [Cosentino’s] Dekton® first came out, we mainly did mitered edges to keep the veining on the top over the edge, too,” says Creek. “Now, people do it on all materials just to have a thicker looking stone on their cabinets. And we do it out of convenience, because if you’re good at it and your saw is set up correctly, it’s fast.” He adds that now that Countertops of Memphis has done several jobs in 2cm Dekton, they’re selling jobs with no edge, which has become popular in Europe. By comparison, Creek says the shop is making fewer waterfalls, which typically show a mitered edge. While not saying they’re doing fewer waterfalls, the others say in general mitered edges are showing up everywhere. “It doesn’t matter what the product is,” says Malisanti. “It’s where people want the look. It might be on a sintered product, it might be on quartz, it might be on stone.” “We do mitered edges of 3” for anyone who wants it on their tops,” Le Puma says. “It’s mostly on stonework,” says Bratti.

"We still have some funky edges that we don’t have cutters for from the old days. However, the ability to do it with a (CNC) router makes it a simpler process.”

Tony Malisanti Malisanti Inc. Great Falls, Mont.

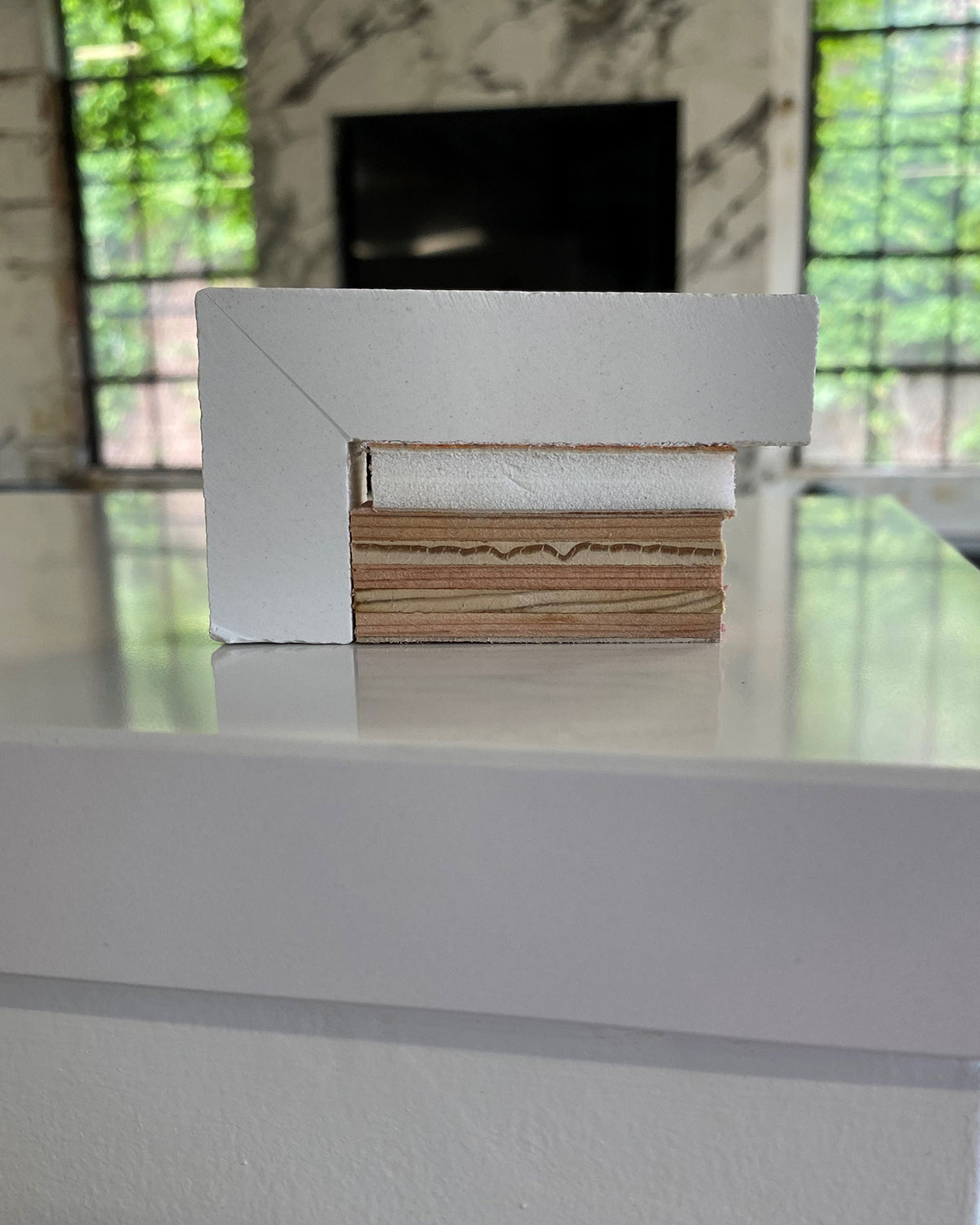

Here's a 2cm Dekton mitered-edge cross section, showing the joint as well as the full substrate buildup used on that combination of material thickness and edge height. (Photo courtesy Countertops of Memphis)

Imagination

As Creek says, if your saw is set correctly, cutting miters can be fast. And, what if it isn’t as accurate as possible? Say there’s a slight gap between the edges. Then what? “It depends on the application,” says Malisanti. “If that added thickness can be laminated old school and they can save some money, they’re happy.” He notes that usually the adhesives and their coloration don’t make it a problem. “Of course, we try to make it as perfect as we can, but the reality is it doesn’t always work out,” he adds, using mitered returns done on the jobsite as an example. Creek says with his shop it’s certainly not intentional, but sometimes things happen. “Whether it’s a problem with the saw or the materials, we might have a bigger gap than we’d like,” Creek says. “A good color-match glue really helps with that unless it’s a heavily veined and contrasting material. We always try to do a 32nd of an inch or less with the glue line.” On the other hand, Bratti says with his high-end customers the goal is to turn out joints that aren’t even discernible as joints. As for the future of countertop edges, with many customers going for mitered or eased edges, is the triple ogee fading into the sunset? What lies ahead? On the one hand, Creek says he believes the trend will continue toward more eased edges, simply because it’s easy for shops to handle. “What’s going to effect that will also be what people are seeing in architectural and design magazines,” he says. “Because of all the technology we have, we could also be doing some incredible things.” Le Puma is willing to go even farther out on a limb than that. He notes that solid-surface countertops are already thermoformed, and he expects technology may do the same with quartz surfaces in the future. “The question becomes, ‘Can we bend this top to come around this corner?’” Le Puma says. “Obviously, you would have to reduce the thickness of the quartz, and you’ve got to be able to heat it up, and you’ve got to be able to hold it into form. From a design aspect, I think it’s a matter of softening up the corners.” Although he doesn’t mention bending quartz, Malisanti says he thinks the industry is going to be a little more creative when it comes to edges. “The tooling is going to make it possible to do more things,” he says. “At the same time, it’s going to take the human factor out of it a little bit more. One of the inherent advantages of natural stone is being able to do these different types of edges, and I think we can use that to our advantage.” Bratti takes it a step further than tooling and sums it up in one word: “Imagination.”