Battle on Biofilm

Solving a Sticky Situation at the Jefferson Memorial

Previous page and above photos courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts

By K. Schipper

WASHINGTON – There’s a paradox about people’s perception of marble that’s sometimes difficult to understand. Many homeowners question whether the material is up to the wear-and-tear of the average kitchen, but builders often turn to the stone to erect structures that last centuries. Occasionally, the two faces of marble collide … although not intentionally. The cleaning of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, scheduled to be completed this September, is due mainly to a surface problem that has proven nowhere as easy to resolve as an errant red wine stain or etching from a misplaced lemon. And, it took some high-tech equipment to bring the structure back to its radiant white look.

The memorial honors Thomas Jefferson, the nation’s third President, who is probably better remembered as the main author of the Declaration of Independence. It’s also a relatively young structure when compared to other Washington stalwarts; set almost due south of the White House on the city’s Tidal Basin, the memorial was dedicated April 13, 1943, on what would have been Jefferson’s 200th birthday. The structure itself is a stone-lover’s dream. The exterior, including the domed roof, pediment, supporting columns and steps, is made of Vermont Imperial Danby marble. The interior utilizes white Georgia marble for the walls, pink Tennessee marble for the floor, and Indiana limestone for the dome’s interior. Thanks to its construction, exterior maintenance on the memorial over the years is generally cyclical, with an emphasis on masonry cleaning, re-pointing of faulty mortar joints, masonry repair, roof replacement and drainage improvements. However, around 2006, National Park Service officials and the visiting public began noticing some discoloration of the memorial’s exterior – mainly the dome – which tops off at 130 feet above the Tidal Basin. “We kept taking photos of it every year, and noticing it getting worse and worse and worse,” says Jacquelyn “Lindy” Gulick, architectural conservator for the National Mall and Memorial Parks. “It became really apparent on the dome and pediment, and we started to see it on other marble features, so we knew it was growing.” The it in this case is a biofilm, which can be bacteria, fungi, or protists. (A good example is dental plaque.) Regardless of its composition, the cells in a biofilm stick to each other and often to another surface, with the whole thing becoming embedded in a slimy extracellular matrix. In 2014, the National Park Service (NPS) began working with microbiologists studying biofilm to identify the substance and determined something would have to be done as the formerly pristine building – particularly the 10,000 ft2 dome – was becoming increasingly dark. The very nature of the problem guaranteed there wouldn’t be a quick solution. The location of the memorial near the Tidal Basin and the presence of the biofilm –known to survive in harsh urban environments, as well as against chemicals and cleaning products – prompted NPS officials to rule out of the use of chemicals.

EverGreene's Amber Edmonds applies steam near the dop of the memorial dome. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

Claire Neyland takes the laser to the profile of Thomas Jefferson. Note the crack in the nose. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

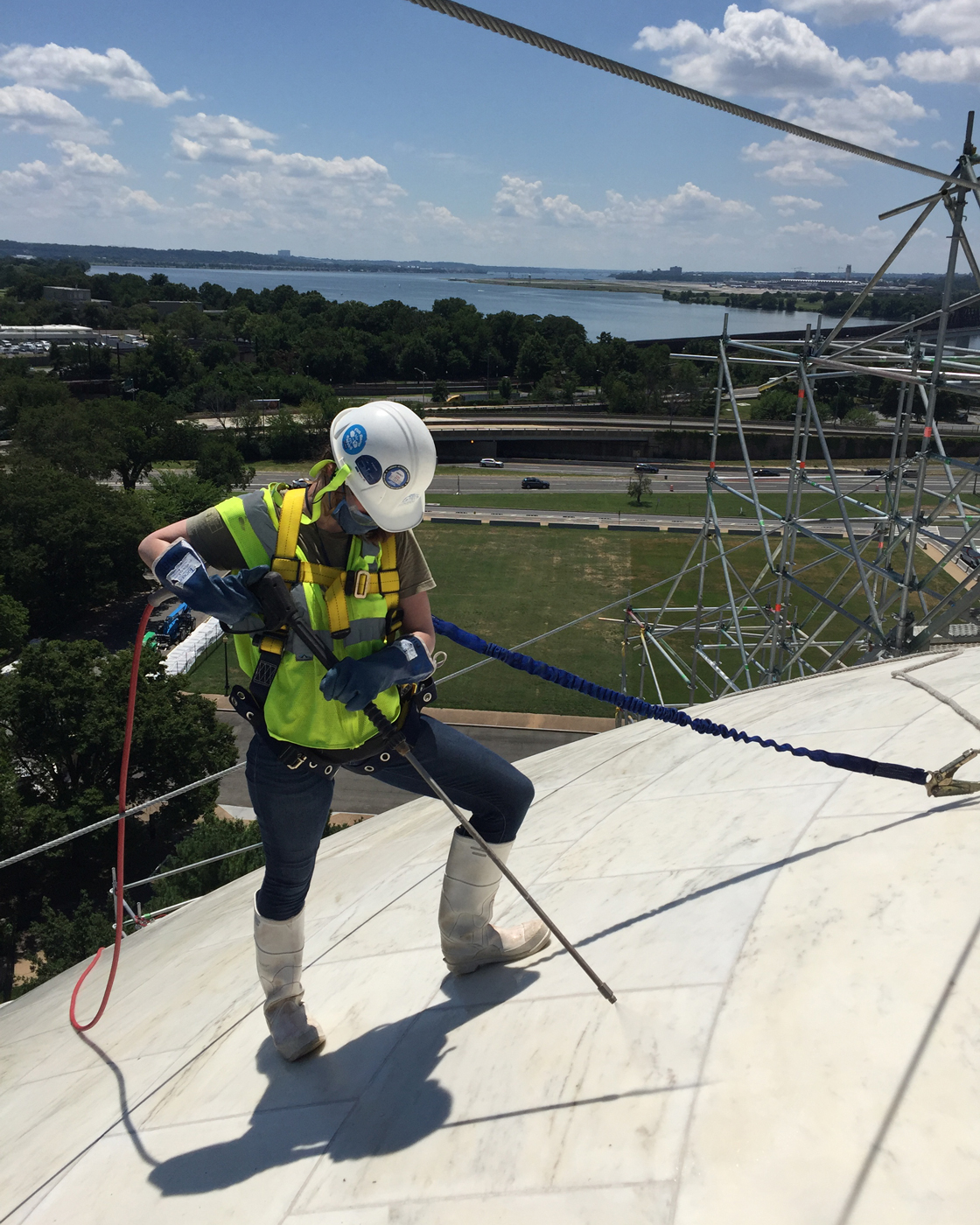

Mia Maloney keeps her footing while putting the steam to the marble dome. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

The NPS’s cleaning project eventually included replacement of two flat upper and lower roofs that circle the dome, as well as the waterproofing under the marble tile roof covering the portico or front entry of the memorial. It also included re-pointing many liner feet of faulty mortar joints, and stone repair under the portico and along the colonnade ceilings. A later expansion of the cleaning project involved the rest of the exterior marble, along with funding of a testing phase to find a method (or method) to see what was going to be effective on the biofilm. Options included various iterations of water, including steam. Gulick says the NPS has a preservation crew that tested some of the non-chemical methods for cleaning the marble. “They did some low-pressure methods and some power-washing to see if that would work,” she says. “That was not successful in removing the biofilm. They also tested some detergents and some biocides, but they also weren’t successful.” Still another option considered was laser cleaning – a process that has grown increasingly popular among conservators in the almost 50 years since it was developed, but something the NPS couldn’t do in-house. That work, conducted by Forest Park, Ill.-based Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio Inc., (CSOS), involved a 1,000 ft2 “slice” of the dome. “It looks almost like a piece of the pie was cleaned on the memorial dome,” says Gulick. “It let us see how the laser was working at removing the biofilm. After that, you could look and see how clean the surface was in our test panel versus the uncleaned part.” At that point, the work was bid, specifying the laser cleaning. Grunley Construction of Rockville, Md., was chosen as the general contractor, with EverGreene Architectural Arts of Brooklyn, N.Y., as the conservator subcontractor. Mark Rabinowitz, a senior vice president with EverGreene based in District Heights, Md., explains while laser cleaning by conservators has become more-common, there still aren’t many firms capable of taking on such a job, and the company has relationships with many general contractors. “Laser cleaning has become more common in architectural settings, although I wouldn’t say it’s standard,” he says. “It’s been used for a long enough period of time that more people have had more experience with it, and the cost of the equipment has made it more available.” As their use has become more common, lasers have also lost their reputation of being a “death ray.” In fact, the use of the Nd: YAG-Q-switched laser offers a delicate method for removing soiling and stains on buildings, monuments, and sculptures. “The largest project we’ve done with laser cleaning was at the Canadian Houses of Parliament in Ottawa,” says Rabinowitz. “We specified and oversaw the laser cleaning of the entire exterior of the building, which was massive. We’ve also done laser cleaning on the U.S. Capitol and the Russell Senate Office Building, as well as several private projects. However, it’s still a specialized kind of work that takes a specialized client.”

Mohamed Abodour works on the side of the Jefferson Memorial. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

Maria Hardman applies the steam as she finishes a pass on the marble dome. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

Walter Kesaris continues some deft application of the laser on Jefferson's face. (Photo courtesy EverGreene Architectural Arts)

It’s also not a “shoot it and go” type of situation. Along with the training of employees and safety requirements to protect both the operators and the public, each job requires an assessment to determine how effective the laser will be in any given project. “Those can vary dramatically,” Rabinowitz says. “The lasers have a lot of parameters that are adjustable, and there are very complex and sophisticated criteria that can be selected. And each cleaning condition is different and requires different tuning of those criteria.” Once tests determine the most-effective criteria for a job, he adds it’s a fairly simple process, but a slow one. A good pace of work is 2 ft² per hour. In this case, what also makes its use special is that Rabinowitz says it’s not often used for cleaning bio-infestations because the wavelength is not absorbed by water, and biofilms are mostly water. However, once onsite, EverGreene’s experience on the project led to the modification of the original specifications of the work. That meant going to a four-step process that began with a warm water wash to get rid of the dust and soil, as well as remnants of the cutout from the joint removal. That was followed by a steam process, laser ablation, and then a final steam after re-pointing. Work began in 2019, and both Rabinowitz and Gulick say the approach EverGreene is taking seems to be working. “What we see is that where the dome has already been cleaned over a year ago, it’s actually getting whiter,” says Rabinowitz. “It’s certainly not re-soiling, which would be more common for a bio-infestation, which tends to return pretty quickly.” However, Gulick says a few small areas were left uncleaned on the roof to serve as control samples for on-going research. “We can continue to take samples from an uncleaned stone which is right adjacent to a clean stone to try to understand the differences between the DNA and RNA of the biofilm,” she says. “We don’t want to be down this same road in 10 years; we don’t want to look at the dome and not understand what’s going on.” And gaining greater understanding of the biofilm may be critical as it’s appearing on other structures. Gulick says a different biofilm has appeared on the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. It, too, is made of Vermont Imperial Danby marble, although the problem isn’t limited to that marble or our nation’s capital. “There are microbiologists and other scientists and conservators who are trying to figure out more about this microbial community that’s found all over the world,” Gulick says. “Right now, we really just have questions. Is it caused by changes in weather patterns? Is it more humid? Is the air cleaner with less particulate matter? Is it less acidic? We just don’t know.”

Even a Great Man May Need a Nose Job

WASHINGTON – There are always side issues with any major product. At the Jefferson Memorial, they included the Sage of Monticello’s nose. While ridding the memorial dome of biofilm was the main focus of this cleaning job, other areas of the exterior were also given the once over. Mark Rabinowitz, a senior vice president with EverGreene Architectural Arts, says a more-common use of the laser is attacking the gypsum crust which frequently appears on stone, which the memorial also exhibited. “These are areas where the stone is exposed to atmospheric pollutants,” he explains. “A black crust forms which is easily cleaned off the surface with lasers. It’s a chemical conversion of the marble, not biological.” One area that showed some need for the removal of both the biofilm and the gypsum crust was in the sculpture group under the triangular pediment that marks the portico entrance to the memorial. “They did some general cleaning there,” says Jacquelyn “Lindy” Gulick, the National Park Service architectural conservator. “They removed mud daubers and insect nests and just

Before

some general soiling. The gypsum crust was mainly under some of the egg-and-dart molding and other decorative elements.” And then there’s the issue of Jefferson’s nose. Not the one on the 19'bronze statue that serves as the memorial’s centerpiece, but in a sculpture group called “The Committee of Five” that’s part of the triangular pediment over the portico. It portrays the five-member committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence submitting its report to the Second Continental Congress. “The entire group was in really good condition,” says Gulick. “However, there was a crack in Jefferson’s nose, so we injected a restoration grout with a syringe and needle. Apparently that crack has been there since the 1990s, and we just took care of it, so it doesn’t get worse.” Although the cleaning project is scheduled to wrap up in September – or October at the latest – it won’t mark the end of construction activity at the Jefferson Memorial. Later this fall work is scheduled to get underway on a privately funded project to upgrade the underground restrooms and museum at the site to make them more accessible. – K. Schipper