THE BIG LIFT

"A Need for More Mobility in the Shop."

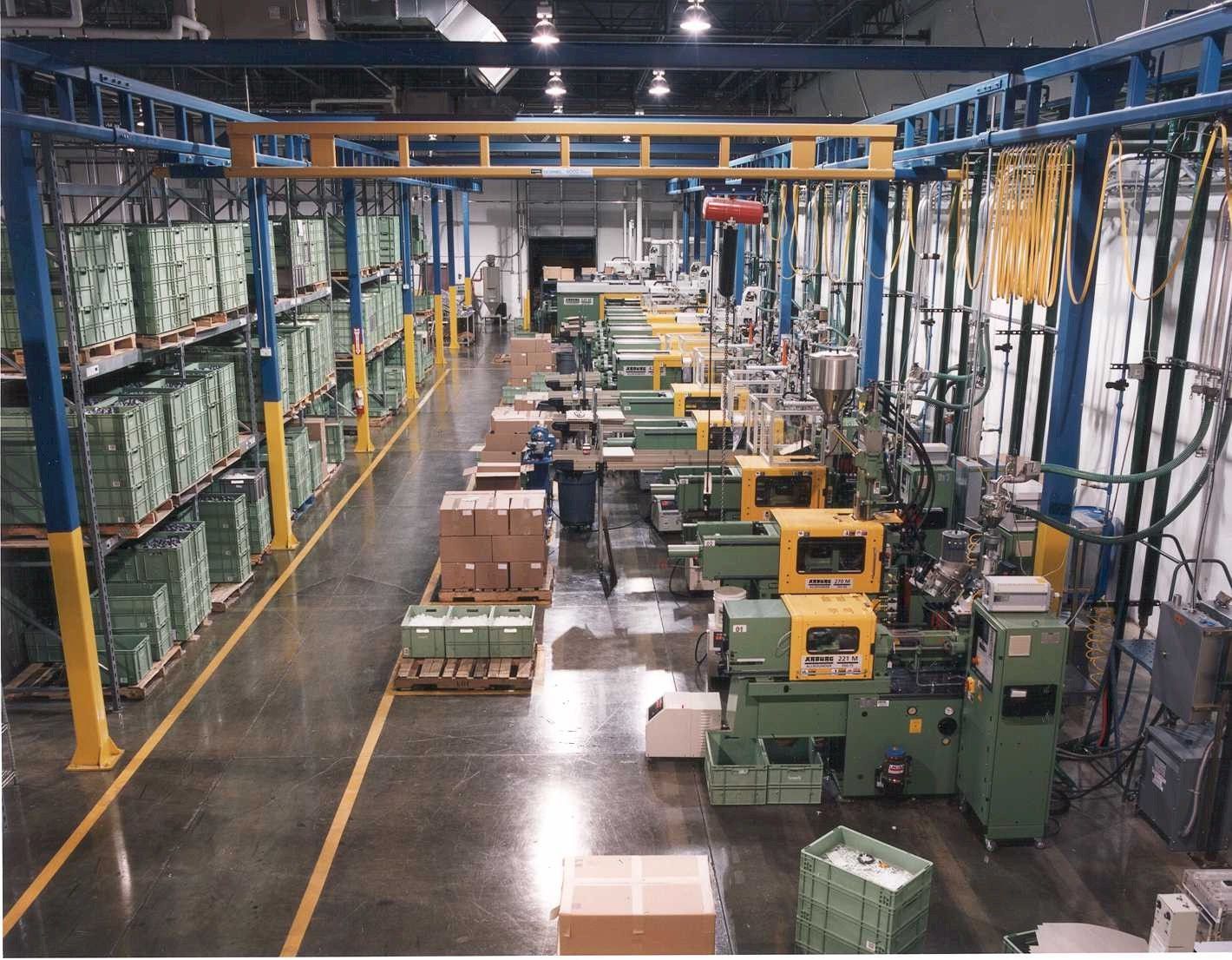

Photo on this and previous page courtesy Corbel

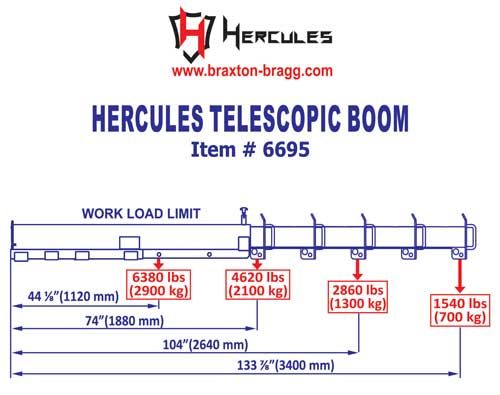

“A new shop would have to have a forklift boom.” Matt Maples, Braxton-Bragg

By K. Schipper

Hard surfaces aren’t the easiest materials to move around.

Even handling a backsplash is going to require some muscle. Powering a slab from the yard or warehouse onto the table of a bridge saw or CNC will take more than a few extra sessions at the gym.

It’s the reason one of the most-common pieces of equipment across the industry is a forklift with a boom attachment. It’s a comparatively inexpensive way to move slabs, but as a shop grows, it may not be the best way to do that part of the job.

The trick is knowing when it’s time to upgrade and getting a system that will maximize your space and production.

A BOOMING APPROACH

Does every stone fabrication shop open its doors with a forklift and boom attachment for moving slabs? There are a few exceptions, but probably not many.

“A new shop would have to have a forklift boom,” says Matt Maples, product manager for Knoxville, Tenn.-based Braxton-Bragg. “There really is no other way to move slabs without one, although there are several options when it comes to the attachment.”

Whether it involves a gravity lifter, straps or a vacuum lifter, the boom is a key part of the equation, and will likely be extendable to allow a better reach for loading and unloading trucks or unpacking a container.

However, Scott Schuster, director of training for Virginia Beach, Va.-based Regent Stone Products notes that there are some issues that can arise using such a combination. One is getting just the right boom for peculiar factors, such as having lower-than-normal door heights at a shop, or the need to load and unload material from relatively different heights.

“There’s also typically a minimum of weight to the forklift to be able to move a slab,” he says. “If you’re moving a slab on a boom, the forklift needs to be three-to-four times the weight of the slab. Bigger is better, but then you lose maneuverability, and the expense can be an inhibitor.”

In general, though, Schuster says if you’re feeding one saw, a forklift with a boom is going to be enough to keep jobs moving.

As this chart shows, forklift booms are hardy ... but also have limits.

“As the operation grows, there are different needs.” Scott Schuster, Regent Stone Products

The addition of equipment to increase production is probably one of the best indicators that it may be time to step up to something beyond the forklift-and-boom combination.

“As the operation grows, there are different needs,” says Schuster. “That includes the building configuration and the machines. You might have limitation on where a forklift could travel, or you have machinery placed in such a way it wouldn’t have direct access to the forklift.”

“If you find you have a bottleneck somewhere and you’re waiting on a lifting solution in the shop that’s holding up production,” says Adam Nelson, product manager for Norcross, Ga.-based GranQuartz, “it’s probably time for something more-sophisticated.”

Both Nelson and Rob Beightol, director of marketing for Fishers, N.Y.-based crane manufacturer Gorbel, agree that another good reason to look at an upgrade is the physical health of employees,

“They may be trying to do something with a piece of equipment that’s not necessarily designed for it,” says Beightol. “They can start to see some strain on their workers, who may be out with back pain or shoulder pain. If productivity is going down because a worker is injured or not 100%, it’s time to look at different ways of performing the job.”

“It’s fairly subjective, but if somebody gets hurt, that can be added impetus to adding a more-sophisticated lifting solution,” says Nelson. “Safety should be the number one concern for everybody, and an injury can sometimes do that.”

Jib and gantry cranes fill needs between a simple forklift boom and a heavy-duty overhead system. However, as this video illustrates, a solution in some industries may not fit with hard surfaces.

Gantry Crane: “You don't want it moving and rolling on you.” Adam Nelson, Gran Quartz

A QUESTION OF FLOW

If any of these reasons to consider an upgrade rings a bell, don’t worry; there are plenty of crane options available, although some work better with stone and quartz slabs than others.

A common step-up from a forklift and boom in some industries is a gantry crane. Andrew Litecky, president of Clarksburg, N.J.-based Shupper-Brickle Equipment Co., describes a gantry crane as “a swing-set on wheels.”

“You have a hoist and a trolley in the beam, and you can push it around to different places,” Litecky says. “However, it’s the poor man’s crane system. It’s inexpensive, but like a forklift, it requires aisles and you’re displacing floor space for the wheels.”

GranQuartz’s Nelson says safety can also be a concern with a gantry crane.

“They’re rarely used in stone shops because of the capacity” Nelson says. “You also don’t want it moving and rolling on you, because there’s a danger of tipping when they move. You’re better off with something a little more fixed than that.”

A crane that meets that fixed description might be a jib crane. Mounted to a pillar or a wall, Litecky describes it as an arm that comes out, with a hoist and trolley that run back and forth on the arm. Depending on the placement, coverage could be anywhere up to a complete circle.

Nelson notes that a jib may be a little less expensive than a work-station crane, but the installation may cost more. As for the advantage of one over the other, “It depends on how many pick-points a shop has and what flow they have to the work.”

Probably the system that offers the most options is an overhead system. Those vary in capabilities and costs, with the most basic being a work-station crane.

“It’s basically a giant erector set where it’s put together within certain finite parameters for height and width, with a rather indefinite length,” Litecky explains. “The X and Y directions are the bridge and the trolley, and they get pushed and pulled by the operator very, very smoothly and very easily.”

For the Z direction (height), the workstation crane features an inexpensive electric chain hoist. Properly designed, Litecky says such a system can easily handle two tons. Shop height does have some influence in what can and can’t be installed, and the width of the area served shouldn’t be more than 30’.

For even larger areas – and for heavier weights -- Litecky says the only option is a full-fledged bridge crane, which would be fully powered and operated with a wireless remote.

One important consideration in installing any crane system is the building itself, and it’s not just ceiling heights.

“Retrofits can be difficult because of several factors,” says Braxton-Bragg’s Maples. “Most crane systems require a certain depth of concrete for the systems to be safe. Not all buildings are designed to be granite shops so, in some cases, a structural engineer would be required to mitigate risk.”

Shupper-Brickle’s Litecky says generally it’s easier to design a crane system into a new building, something worth considering if that’s on your horizon.

“To actually load the building frame with a crane, you have to have it designed in,” he says. “That’s why most of the time you have to have a freestanding system.”

Nelson notes that a jib may be a little less expensive than a work-station crane, but the installation may cost more. As for the advantage of one over the other, “It depends on how many pick-points a shop has and what flow they have to the work.”

Probably the system that offers the most options is an overhead system. Those vary in capabilities and costs, with the most basic being a work-station crane.

“It’s basically a giant erector set where it’s put together within certain finite parameters for height and width, with a rather indefinite length,” Litecky explains. “The X and Y directions are the bridge and the trolley, and they get pushed and pulled by the operator very, very smoothly and very easily.”

For the Z direction (height), the workstation crane features an inexpensive electric chain hoist. Properly designed, Litecky says such a system can easily handle two tons. Shop height does have some influence in what can and can’t be installed, and the width of the area served shouldn’t be more than 30’.

For even larger areas – and for heavier weights -- Litecky says the only option is a full-fledged bridge crane, which would be fully powered and operated with a wireless remote.

One important consideration in installing any crane system is the building itself, and it’s not just ceiling heights.

“Retrofits can be difficult because of several factors,” says Braxton-Bragg’s Maples. “Most crane systems require a certain depth of concrete for the systems to be safe. Not all buildings are designed to be granite shops so, in some cases, a structural engineer would be required to mitigate risk.”

Shupper-Brickle’s Litecky says generally it’s easier to design a crane system into a new building, something worth considering if that’s on your horizon.

“To actually load the building frame with a crane, you have to have it designed in,” he says. “That’s why most of the time you have to have a freestanding system.”

Workstation Crane: “It’s basically a giant erector set. ” Andrew Litecky, Shupper-Brickle Equipment Co.

A BIT OF GUIDANCE

Like just about any other business-related purchase, making an investment in a material-handling device such as a crane isn’t to be entered casually. Fortunately, there are plenty of people out there available to help and educate a would-be buyer.

“Any company that sells this type of equipment should have a knowledgeable representative that can help guide you through your decision,” says Maples.

Gorbel’s Beightol notes that his company works with an extensive dealer/distributor network.

“If somebody calls us, we’ll take as much information as we possibly can, and then try to filter that through our distributor network,” Beightol says. “Our goal is to get somebody onsite who can do a walk-through and determine what the needs are.”

He adds that the most-common Google searches for these devices are “crane builder” and “overhead material handling equipment.” And, in doing that online search, Litecky – whose Shupper-Brickle is one of Gorbel’s dealers -- says aim to find someone to work with who’s local.

“It’s important to have a local guy come in, pull the tape and make a presentation to you,” he says.

Having that local company is helpful for other reasons. One is training, although unless it’s a bridge crane Beightol says typically the focus is on the lifting device that goes along with the system.

“If it’s not a motorized system, there really isn’t any specialized training required,” says GranQuartz’ Nelson. “Whatever is attached to the hoist – whether it’s a vacuum lifter or a lifting clamp – is going to require more training than the crane itself.”

Still another is maintenance. Having a local technician who can come in once a year, do an inspection, handle any needed maintenance and provide proper OSHA certification is very important, says Litecky.

The bottom line: Anytime a shop has changed the workflow or wants to expand or create a different configuration, it’s probably a good time to look at a material-handling device.

“More machinery means more production which, in turn, means a need for more mobility in the shop,” observes Braxton-Bragg’s Maples.

Or, as Beightol says, “Our dealers are trained to go in and look at everything from the beginning to the end of the process to see just how something is manufactured.

“That way we’re able to make suggestions to increase efficiency and reduce the strain on the workers.”