A House of Worship for All

The Bahá‘í Temple of South America in Chile welcomes all faiths under a unique shelter of marble and glass.

Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com

PEÑALOLÉN, Chile – Some architecture startles with exaggerated lines and features, while other buildings use steel and glass to be cold and bold.

And then there’s something about the The Bahá‘í Temple of South America here that’s, well, soothing. Nine elongated petals reach for the sky, reflecting surrounding colors to create a calming effect both inside and outside the building.

It’s the kind of architecture that seems easy, simple and natural. Of course, nothing about the construction of the Bahá‘í Temple was easy and simple … but much of it is natural, under a canopy of Portuguese marble.

The project took Toronto architect Siamak Hariri 13 years to complete, from original planning to final construction. Unlike many long-term projects involving temperamental clients and a constant flow of change orders, the long germination stemmed from the nature of the building, its location and the search for the right materials.

Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com

Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com

Commissioned by the Universal House of Justice, the supreme ruling body of the Bahá‘í Faith, the Chilean location is the eighth and final continental temple for the Bahá‘í Faith. (The oldest, completed in 1953, is in Wilmette, Ill.).

Bahá‘í religious laws shape the design of temples. Unlike houses of devotion of other faiths, people of any religion may worship at a temple. Doors must be open to anyone regardless of religion or any other distinction. Temples need to be a place of community and inclusion.

There’s also one particular detail – or, to be exact, nine. The Bahá‘í faith associates the number nine with perfection and unity.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, one of the faith’s great leaders at the turn of the 20th century, directed that Bahá‘í houses of worship include a nonagon, or a nine-sided shape.

Hariri Pontarini Architects won the design competition for the project, selected from 185 entries coming from 80 countries, in 2003

The temple opened much later … as in October 2016.

Some of the long time-lapse came with funding the $30 million structure. Only Bahá‘í members can contribute to the building of a temple, and fund-raising efforts involved local members and Bahá‘í faithful worldwide.

Courtesy EDM

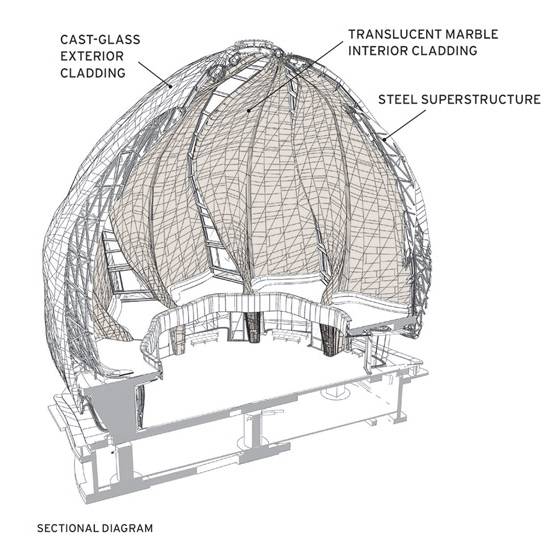

Another test of design came with the inclusion of the nonagon. Other Bahá‘í temples incorporate a dome with nine sides; all included nine entrances. Hariri’s design included both ideas with nine vertical wings coming together at the top in a dome-like shape.

Keeping the wings upright, however, ran into a problem: earthquakes. Chile’s sometimes violent temblors (the 1960 Valdivia quake registered between 9.4-9.6 magnitude, the strongest ever recorded on earth) could spell doom for the design’s light and airy structure.

The answer came with nine slim-profile-steel superstructures for the wings, with all of them fitted to concrete pads sitting on elastomeric seismic isolators. Using a pendulum-isolation design, the building can move up to nearly two feet (23.6”) during an earthquake. (Another major structure using similar isolation techniques is Apple Park in Cupertino, Calif.)

The design also called for translucent wings to contribute a light and airy feel to the building. Originally, Harari had a natural answer … with alabaster.

Cladding the wings in alabaster didn’t fly for several reasons. Air pollution in the Santiago area would quickly besmirch the stone, and rain would pose erosion problems for the soft (Mohs 3.0 or so) material. Heat also is an enemy; alabaster also decomposes in temperatures above 122°F.

The solution came in two steps.

For the outer surface, the architect worked with Toronto’s CDG Glass and glass artist Jeff Goodman of East York, Ont., in a four-year process to develop a cast-glass product that’s tough and translucent. Covering all the wings involved 1,129 unique flat and curved pieces.

Courtesy EDM

Natural stone came into play with the temple’s interior. Hariri found marble sourced from Estremoz, Portugal, that met the criteria for translucency.

Paris-based EDM Ateliers de France headed up fabrication and installation, cutting more than 9,000 pieces by waterjet. Unlike standard cladding jobs, each piece had a unique shape, as determined by computer modeling.

EDM used more than 1,200 metric tons of the Portuguese marble in a job that took 15 months to cut in Europe.

Courtesy EDM

Courtesy EDM

Courtesy EDM

Courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com

Montage courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com

Since the temple’s completion, Harari received several honors, including the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Innovation Award and last year’s Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) International Prize.

The temple seats 900, but its structure and surrounding gardens now make it an attraction drawing many, many more. More than 1.4 million visit the temples and grounds annually, and more than 36,000 arrive on busy weekends.

v2com newswire assisted with the materials for this article.

Photo courtesy Hariri Pontarini Architects / v2.com