That slow-cutting diamond tool may not be dull or worn-out. It probably needs a bit of, well, industrial hygeine.

Dressed for Work?

Photo by Emerson Schwartzkopf / Previous page: Photo courtesy Lackmond Stone

By K. Schipper

In a stone shop, diamonds aren't forever.

Industrial diamonds are harder than stone, but they can get chipped, broken or fall out of a sawblade or CNC tool. Not even James Bond can save the day when the metal in which they’re anchored last indefinitely, and that’s where problems can arise.

The best solution: dress your tools.

“CNC tools need dressing because the matrix wears out,” says Dan Riccolo, owner of Morris Granite in Morris, Ill. “As the matrix wears out, it exposes the diamonds, and when the diamonds are no longer held in place by the matrix, they fall out.”

However, that doesn’t always happen. Particularly with diamond saws, if you have the wrong mix of matrix and stone, the matrix will melt around the diamonds and make them ineffective for cutting.

The same holds true for the rest of the shop’s metal tools. On a CNC, that’s usually positions 1-4, and sometimes 5, depending on the manufacturer of the tooling, says Eric Gertken, a product specialist with Salem Distribution in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“It depends on the profile of the tool itself and the range of materials you run with it,” Gertken says. “Some natural granites can be more-abrasive compared with engineered materials. That helps keep the tool open and performing.

“If you’re running a lot of the engineered stuff you may need to dress more frequently. The same is true if you’re running some of the more extreme stones, like the quartzites. They will require more frequent dressing.”

Blades, fingerbits and core drills are a bit easier to both assess and dress when that needs to occur.

“The saw will start to perform differently,” says David McDaniel, sales manager for the CNC tool division at Regent Stone Products in Virginia Beach, Va. “The blade will be stressed, and that can result in a poor quality of cut. You can actually hear a blade being stressed; there’s a different sound it will make, and it will also pull more amperage on the saw.”

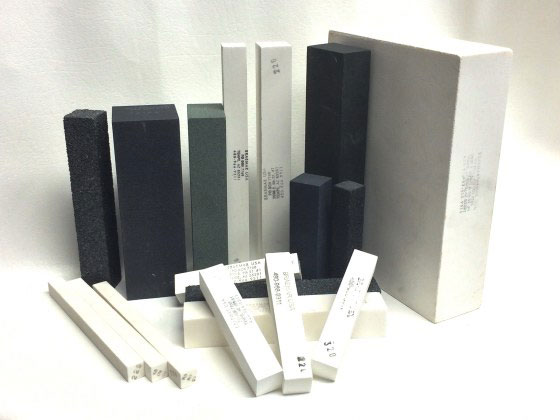

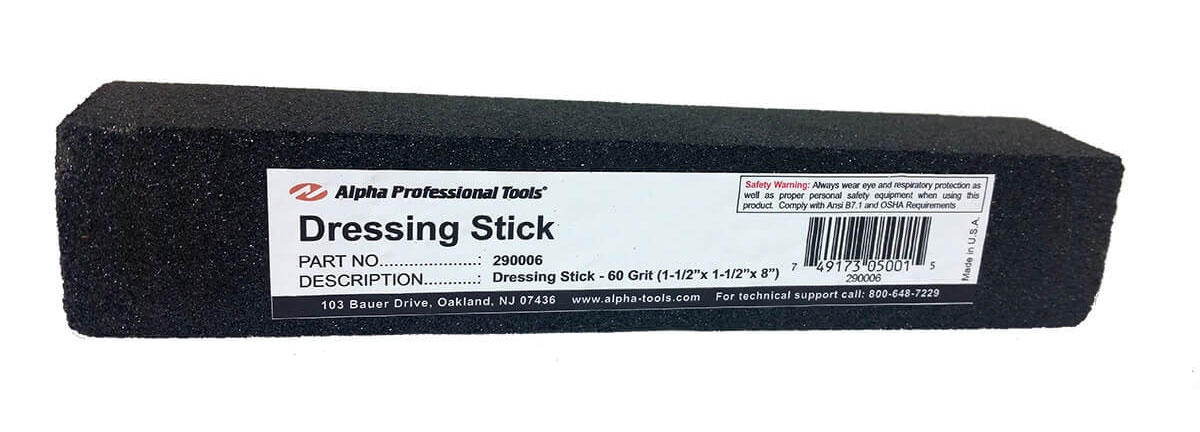

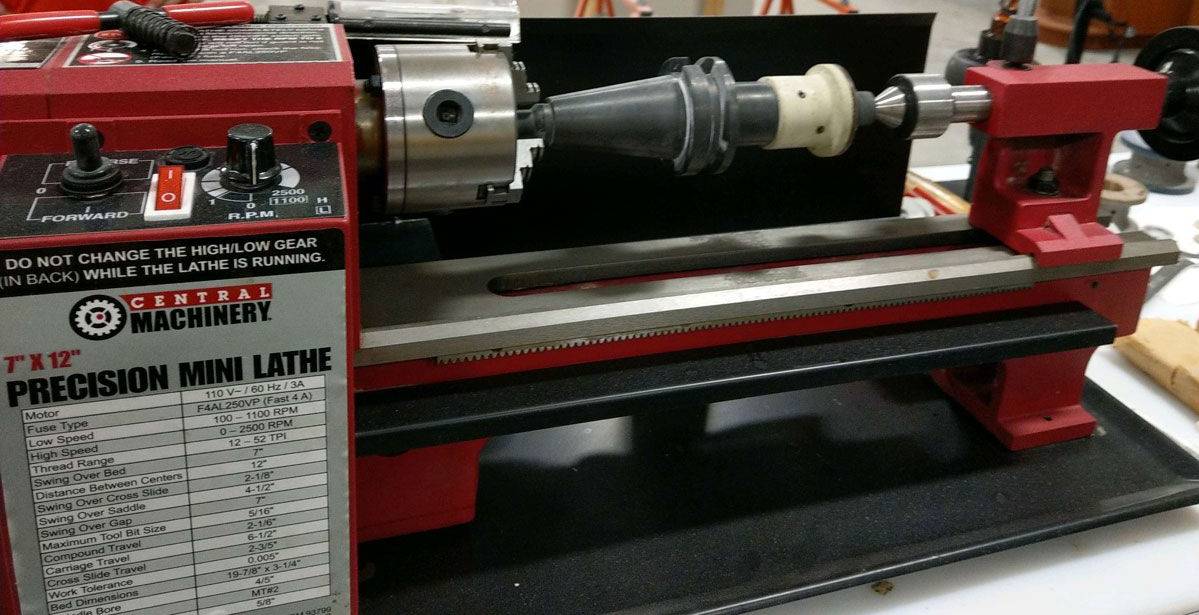

Dressing sticks and blocks are available in a variety of sizes, shapes and abrasive grits. Smaller sticks work well with smaller stationary devices like tile saws and tabletop lathes.

Dressing sticks are not a one-grit-fits-all operation. A silicon-carbide block (above) provides plenty of abrasion with a lower grit to open up the diamonds of hard-driving tools like saw blades. For shaping wheels and finishing tools with edge polishers and CNC machines, aluminum-oxide sticks (below) provide a lighter and more-effective abrading. (Top photo courtesy Alpha Professional Tools®; bottom photo courtesy Lackmond Stone)

Blades, fingerbits and core drills are a bit easier to both assess and dress when that needs to occur.

“The saw will start to perform differently,” says David McDaniel, sales manager for the CNC tool division at Regent Stone Products in Virginia Beach, Va. “The blade will be stressed, and that can result in a poor quality of cut. You can actually hear a blade being stressed; there’s a different sound it will make, and it will also pull more amperage on the saw.”

Although tooling companies sell CNC dressing blocks to address this issue, Riccolo says simply cutting or drilling into a concrete block will work as well.

“Make a couple strokes through the concrete block and dress it that way,” he says. “We use solid ones, but you can use regular concrete ones, and I’ve been in shops where guys cut the floor. Concrete is soft and it will open up most of the bonds.”

And, if a shop is cutting a variety of materials every day, “The blade is typically dressing itself,” says McDaniel.

There are also times when dressing isn’t going to work with blades and core bits, says Gertken.

“If it’s meant to cut wet but ran dry and got really hot, you’ve heated that metal segment too much and it’s hardened it more than it should be,” he says. “At that point you can try to dress it as much as you want, but you aren’t going to get it back to a point where it functions properly.”

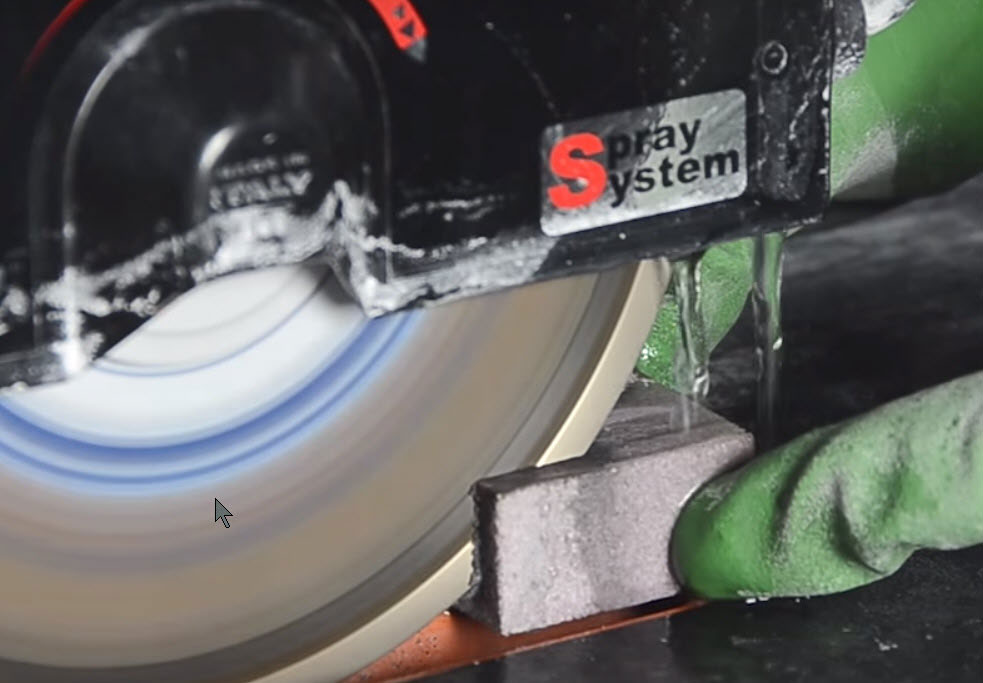

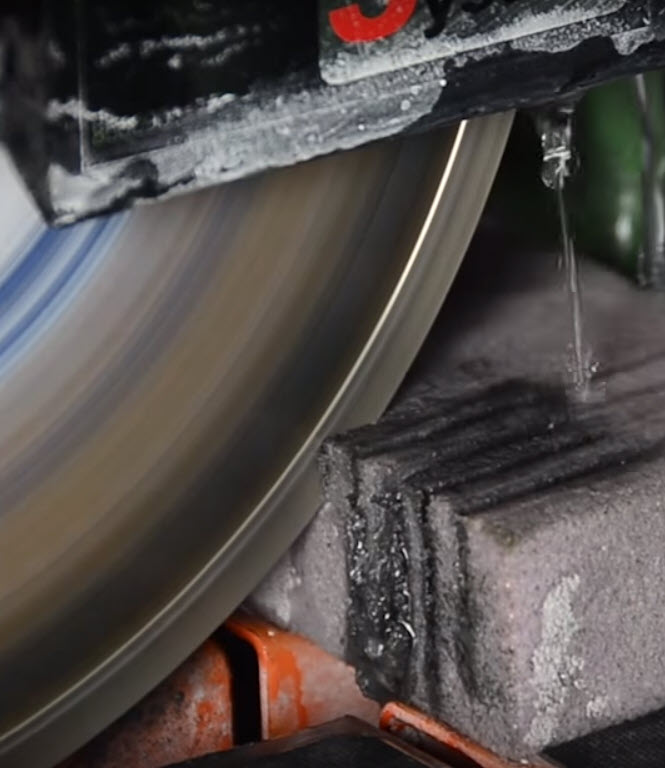

Dressing a blade is a must when cutting materials like quartz surfaces, where the resin binder (or matrix) can leave a glaze on blade teeth. It may take a few tries before the ugly gunk starts peeling off. (Photos via YouTube/Battipav).

Using a concrete (cinder) block is a viable, if not exactly elegant, option for dressing diamond blades and tools. Although this won't blast silica into the air, this method gets messy very fast. (Photo via YouTube/Gazonian Productions)

Dressing the shaping tools on a CNC machine is a bit more difficult, both in terms of determining when the work should be done, and how it’s done.

When it comes to how frequently those CNC tools should be dressed, opinions vary.

Salem’s Gertken says, again, that a lot depends on the profile and the range of materials being shaped.

“I typically recommend people put a counter or flag at about 500 feet as a good reference point to at least inspect the tools to see if they need dressing,” he says. “Otherwise, the easiest way to known is as soon as you have any kind of line in your metal tools.”

Shawn Rice, national sales manager for Lackmond Products in Marietta, Ga., says 500-700 linear feet is a good starting point.

“It depends on the use and it depends on the type of stone,” Rice says. “You want to take them off regularly and touch them up. You also need to pay attention to them. If a line shows up, if you catch it early you can dress it out.”

Ron Hannah, owner of Cadenza Granite and Marble in Concord, N.C., is more-specific.

“We dress our tools every Friday to a certain extent,” Hannah says. “We run dressing stones down the faces of the tools to take the lines out, and the highs and lows and smooth them out.”

Although it may sound daunting, it’s not all that difficult of a job. Hannah says in his case it was a tool salesman who first trained him on dressing tools and he typically has two or three people in the shop capable of doing the work.

“We’ve been very fortunate to have good tool salesmen,” he says. “It’s not in their best interest to tell us anything, but during the recession our tool salesmen were good to us and taught us how to make our tools last forever. We’ve passed that on to our people.”

While dressing to eliminate the errant line that shows up or help eyeball when a tool is working too hard, it’s not the only step to maintaining CNC tools. Nic Sallis, Lackmond’s general sales manager, says — as with saws — it’s important to keep new diamonds exposed so the tools cut properly, but it goes beyond that.

“On the CNC side you’ll also want to maintain a consistent shape between all the different tools,” Sallis says. “Not only do you want to dress the tools to make sure the diamonds are completely open, but you want to make sure the tools across the line from position 1 to position 7 are of a consistent shape and size.”

There are a couple different facets to that. One is measuring your tools.

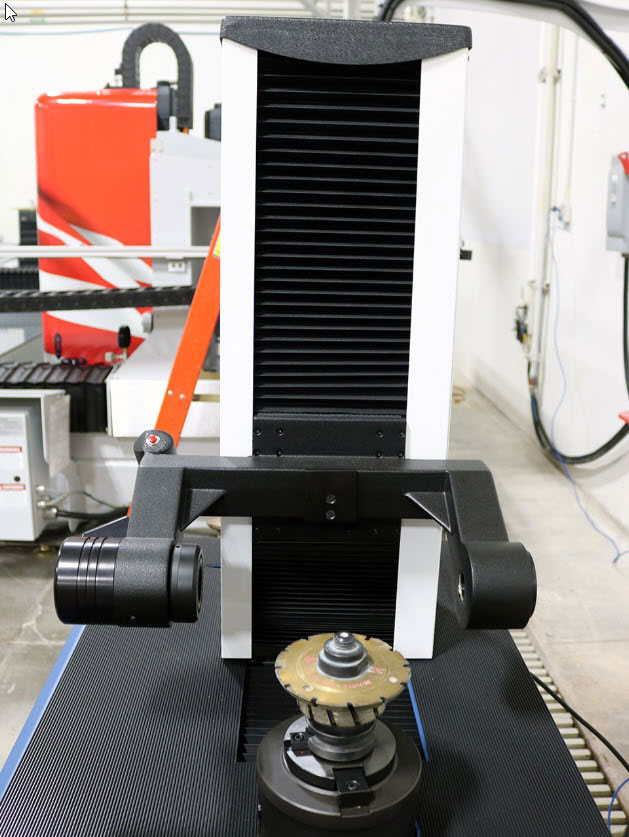

Some CNC machines come with a measuring device. For instance, Hannah notes his Northwood CNC offers LTC (laser tool calibration). Other devices are available, as well. Sallis mentions Fairport, N.Y.-based Omega Tool Measuring Machines’ presetters as another option.

The presetter’s primary role is to determine the length and smallest diameter of the tool to ensure proper stock removal across the set, says Rice. The secondary use is to compare the current shape of the tool to its original profile.

How frequently this needs to be done varies by shop, says Sallis. While an automatic machine should be providing equal pressure and speed with every job, hardness can vary within a slab that will treat the tool differently. Consequently, he says there’s no hard and fast rule on when tools should be measured.

“Ideally, you will measure the tools when you dress them,” he says. “As the tool wears, the diameter decreases. With the decrease in diameter, the CNC must be adjusted to compensate for the wear.”

Even the most-diligent schedule of measuring and dressing isn’t going to keep a tool going forever, but it’s possible to get them reshaped (or re-trued) by sending them to the manufacturer or a machine shop.

While Lackmond’s Rice says some shops never take that step, Salem’s Gertken recommends sending them in about the time the polishers wear out.

“That’s a good time to look at your metals, make sure they don’t have bad lines and the profile shape is still correct,” Gertken says. “If you start up a new set of polishers and they don’t fit very well with your metals, that’s telling you the metals have lost their shape and that’s a good time to send them to be re-trued.”

Rice adds that once tools are re-trued, it should be possible to get another 40% of the tool life out of them.

A tabletop lathe (above) can handle CNC-tool dressing, and can be set to include the tool holder; this shop dresses tools every 200-300 linear feet of use. For tool measurement, some shops are find a presetter (below) a must for proper stock removal by tools on a CNC. (Top photo by Emerson Schwartzkopf; bottom photo courtesy Park Industries)

When it comes to shop tooling, the manufacturers set recommended speeds for their machines and their tools. But how important are those limits when it comes to getting the most life out of a tool?

Probably not as important as you might think. And, running a saw at an inch a minute isn’t going to keep that blade going forever, either.

“The general consensus right now is the faster you can run your tools the better,” says Morris Granite’s Riccolo. “You get more cycles in in a day, and while you’re probably going to wear your tools out somewhat faster, it’s not as fast as the additional productivity you’re going to get.”

Regent’s McDaniel agrees.

“We’re finding that many shops are preferring to run their tools at a higher speed, even though that will cause them to wear faster,” he says. “The return-on-investment on the productivity is better than saving a few dollars on your tooling costs.”

McDaniel notes that labor costs are much greater than the amount most shops spend on tooling, which he says averages five percent to six percent of their expenses. And, Cadenza’s Hannah observes that many shops went to using more automation during the recession, a practice that has continued after the market recovered.

Salem’s Gertken says, too, that other factors besides speed play into the life of a tool, including the materials you’re running and how to balance the feed rate and the rpm to each material.

“If you go too slow, you actually cause yourself more problems because your tools won’t cut properly and they won’t wear properly,” he says. “It won’t necessarily have a horrific negative impact on the life, but you can cause a myriad of other issues, so what you think you gain out of it isn’t worth the extra issues.”

As for the overall care and feeding of shop tools, regardless of whether they’re on a six-figure CNC machine or something you’ve picked up from a local supplier, the best advice, everyone agrees, is to store them in as dry a spot as possible.

“Obviously, rust tends to not necessarily be an issue with the performance of tools, but more an issue with difficulty removing tools from something, like a CNC tool holder, or a sawblade rusting to an arbor,” says Gertken. “Have some sort of tool bench or a peg wall with hooks where you can hang things up and have them out of the water as best you can.”

Although some people choose to coat their tool or the cones with a variety of materials, Regent’s McDaniel suggests staying away from that because it can possibly affect the spindle.

“We recommend that weekly or bi-weekly, wipe them down with something like a WD-40 to clean them,” McDaniel says. “If they’re profiles that are being used the most, simply wipe down the cones and wheels, especially the cones, and then move on. That’s your best preventive maintenance.”