10 Questions With ....

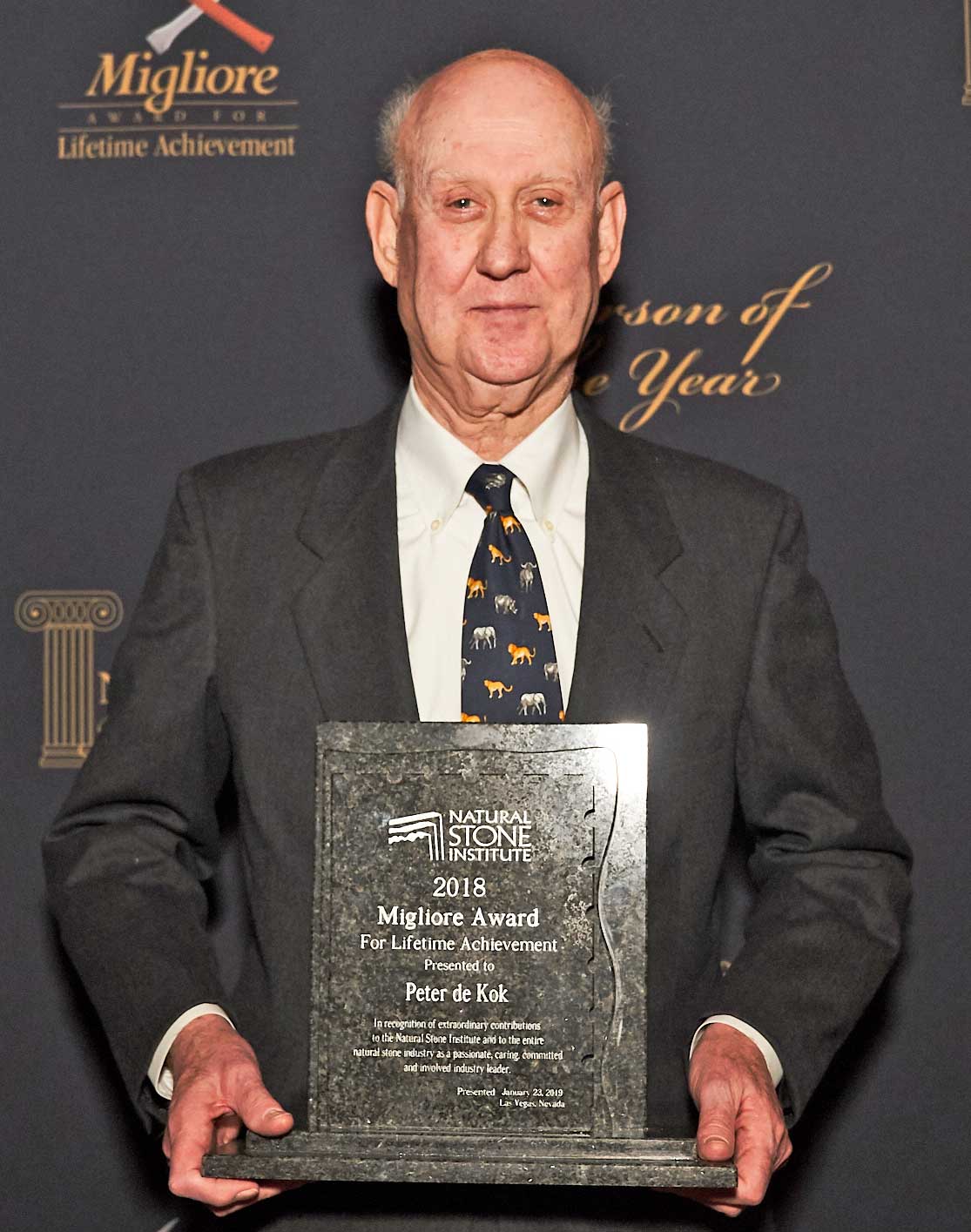

Peter de Kok

There are plenty of ways to describe Peter de Kok. After more than 60 years in the trade, however, there’s one tag that doesn’t suit him at all: retired.

Yes, de Kok stepped away from day-to-day, full-time work some seven years ago with the sale of GranQuartz. He founded the company in the early 1970s and guided it to its position as the largest distributor of stone-fabrication supplies in North America.

He’s not as active in industry associations, after decades of work with the Marble Institute of America (including a stint on the board of directors) and the Building Stone Institute, the forerunners of today’s Natural Stone Institute.

For years, he helped blaze the trail in the United States as an early and constant supporter of StonExpo, now part of today’s The International Surface Event (TISE). He appeared at this year’s event as the latest recipient of the Natural Stone Institute’s Migliore Award for Lifetime Achievement.

To say he's retired, though, is far from the truth. He keeps a weather eye on the industry, especially with his never-ending interest in trade data and statistics. Stone Update renewed a long-running discussion with de Kok on the numbers being passed around, and what they really mean.

Most stone-industry reports cite statistics with “free-on-board” numbers. With the U.S. market, why are those numbers less-than-representative of the market?

de KOK: The reason that it doesn't add up for you is because FOB, or free-on-board, is the value that is used when you put the granite on the boat. You then you have to add freight to that, and some duty and customs clearance. Then inland freight to a slab distributor who puts it on a shelf and has to keep it for some time, after which it is sold to a fabricator. The distributors have to make at least 30% off the selling price, otherwise they won’t stay in business. Thus the sales value becomes totally different from FOB because of all of these additions. Given that the ocean freight is about $2,000/$2,500 for a 20-ton container, that means $120/$125 per ton, plus approximately 5% for clearance and inland freight. By the time it is all added in, you are talking at least 40%/50% more than where you started at FOB. Another calculation is to start from total sales in the countertop industry, say around $12.5 billion and by experience I can tell you that raw material is 30%-32.5% of sales, i.e. about $3.5 billion: this number also includes quartz, so it’s not only stone. All of the numbers are ballpark as our industry is not known for keeping statistics.

So where would you peg the U.S. natural-stone market?

de KOK: A little while ago, I sat down with industry leaders, to include the larger companies in our industry and the various trade associations, trying to figure out total, nationwide industry sales. We arrived at about $27.5 billion. I know that sounds almost unbelievable, but this includes limestone, bluestone, sandstone, Tennessee Crab Orchard, slate, Indiana granite, monuments at retail, and so forth. This is all at retail selling price, which brings you to about that total. So it's a bigger industry than most people assume, employing about 200,000 people, which I believe gives us all something to think about.

What is the effect of all new surfaces coming into market, and what does it change for fabricators?

de KOK: That's difficult to answer as you have the quartz question to consider. Quartz at one stage was, let's just say 10% of the total market, but that has slowly but surely crept its way up to where it is now at perhaps 50%, maybe a little more. Then Mr. Trump comes along and, under a bit of pressure from Cambria, puts a big duty factor onto Chinese quartz, which suddenly drops to the bottom of the pile and granite starts increasing once more. A lot of porcelain people are trying to make their surfaces bigger to make it work for the kitchen countertop industry. And there's no doubt this will have some effect. Will it replace granite? I don't know. Mrs. Jones is a very variable young lady who makes up her mind as she goes along, and it's very difficult to get an accurate prediction of what's going to happen simply because she is a fickle person. It will make a change; how much of a change, I don't know.

As far as tooling — what two developments/improvements made the biggest differences for fabricators?

de KOK: Well I will tell you very simply: Diamond tooling.Our industry depended completely on silicon carbide as a cutting and grinding element, with wire saws and loose-grit polishers. Then came diamond tooling in the mid-70s and put silicon carbide totally out of business. Norton, Union Carbide and/or Carborundum Corporation all shrunk to a shadow of their former selves. That's the biggest development. The next biggest development was CNC, waterjets and automated machinery. Prior to that finishing was all done by hand which takes a long time for an ogee edge, but with a CNC takes no time at all.

There's more amalgamation of fabricators with regional and national holding companies. Is this something you think will continue?

de KOK: A manually operated shop will produce about $125,000 per person, per year whilst an automated fabricator with CNC, waterjet, etc. will produce at least 50/60% more per person, per year. So, Manuel’s Marble Shop with an average of seven workers puts out approximately $750,000 per year, but automate this plant and the numbers escalate dramatically.

Now let's do this a different way. With a reasonably-sized, fully automated shop you can get to $10 million dollars in annual sales fairly easily. Given that the total countertop industry is about $12.5 billion, which, if divided by $10 million, means that 1,250 to 1,500 shops can control the whole market. Unless Manuel’s Marble Shop automates, he will not be able to compete against the bigger companies as his labor and raw material costs are going to be too high.

The second reason is a bigger shop selling $10 million will require $3 million worth of stone which automatically will guarantee a lower price for raw material, than if you are Manuel’s Marble Shop buying at most $250,000 of raw material.

Finally, tooling costs for an automated plant are 2.5% of sales versus 5% of sales for a manual shop. This is because a manual operator puts variable pressure to the diamond tool and wears it out much more quickly than a CNC machine which works very precisely.

Given all the above, a manual shop cannot survive long-term because labor, raw material and tooling costs are simply not competitive with a well-run, automated plant.

Is this a good trend or not?

de KOK: The simple answer is that whether it's good or bad doesn't matter. It will continue. There's no stopping it. If you invented a machine that does the work even more effectively than CNCs, there's nothing to stop a well-run plant buying that new machine either.

What are the most-important things where the United States made a difference in your career and life?

de KOK: The very first thing is that when I came to this country, I had a wife, two children, and 88 pounds of luggage. That is what I started with. I had no college degree. I had been in the granite business for about 12 years. I came over here and I was determined to try and use charter vessels to ship granite block rather than regular liners.

In the old days, you used to ship on a liner before containerization. A liner simply followed a rigid schedule, loading and unloading cargo in each port it called on a regular monthly basis. Chartering means renting at least half of a whole vessel. Chartering rates were about $40 a ton compared with liner rates at $75, but then you contracted for at least 5,000 ton versus perhaps 200.

So, being determined to use charters to transport granite block, at the age of 33 I borrowed $1.25 million to set up this business and within a short time we became the biggest granite block importer in North America.

In those days I competed against MSI, but given that we chartered and he stayed with liners, they could not compete. So he went into a different form of the business whilst, in time, I went into machinery and tools.

Some years ago, I wrote him a letter and I said, “We used to compete against each other with Indian granite when you were working from your basement in Indianapolis. I was working from Atlanta, and I built the business up rather better than you did. But you had the foresight and the brilliance to get into slabs, and you totally wiped me out. I just wanted to compliment you on your perspicacity.”

I met him a few years later at a StonExpo and I shook his hand. He looked at me and said, "You know that letter you sent me a couple of years ago? It sits on my desk and I look at it every day."

Going back many years to when I started in the stone industry at 18 years old, I was apprenticed to the largest granite monument company in Germany and after this apprenticeship I started selling granite block in North America. The stockholders in the company were my dad, my ex-German employer, a Swedish company called Kullgrens Enka and a company in South Africa called Marlin Granite.

One day I went to Germany on a trip for a board meeting and whilst there I walked into the company and saw a diamond saw with a 12 ft blade. That blew my socks right off. I looked at that thing and I could see that it would have an immediate impact over here. So I rang three of my granite customers and I said, "Guys, you have got to come and see this machine. It works 24/7 and it needs no supervision and no labor. It produces a slab as smooth as a sheet of glass."

All three of them flew over to Frankfurt, where I picked them up on a Monday or Tuesday morning and then we ostensibly rode off to go and see this machine in operation. Well, no sooner had they seen that machine than they all three bought one at $125,000 apiece.

Now that was when I got into the machinery and tooling business because the German manufacturer of the saw said he could produce this. But who's going to maintain this thing? And my three customers looked at me and said, "YOU. You got us into this, so you are going to maintain it.”

So I got into the stone-working-machinery business without knowing anything about it, which changed my whole career path, because I started to sell machines and tools, which was the origin of GranQuartz today.

How would you compare the stone industry — international and U.S. — when you first encountered it and its current state?

de KOK: In 1980, the stone industry over here did maybe $6-7 billion. Maybe. Nobody knows because nobody kept records. But the kitchen countertop industry was born in 1990 and it has become $12.5 billion out of about $27.5 billion total, so it represents about 40% of the total sales. Now that did not exist in those days.

In those days, Coldspring was, without question, the biggest granite producer in North America doing in excess of $100 million, followed by Rock of Ages doing about $75 million a year. Add in North Carolina Granite, Vermont Marble, Georgia Marble, Indiana Limestone, Bluestone and Slate producers, plus the total monument industry and industry-wide sales might have been about $7.5 billion, although no one knows for certain as record-keeping was appalling.

On an international basis the same thing is true, whether one looks in the U.K., Europe, monuments and building stone were the focus of the industry until around 1990 when granite kitchen countertop started, originating actually in Switzerland and then spreading worldwide very quickly.

As I have said before, in the Seventies I was importing stone from South Africa, Rhodesia, India, South America, Scandinavia and exporting Dakota Mahogany to Scotland and Elberton Granite to Japan, Korea, Taiwan. So the business was international in the mid-seventies, but became much bigger after the advent of the granite kitchen countertop industry which started using huge volumes of thin stock, which was helped dramatically by containerization.

Are we really looking at a “stone” industry today? Have other options made it something else for fabricators and others?

de KOK: I would say that you are probably correct in one sense that we use 50% of something else other than stone for kitchen countertops. However, for a building it's still mostly stone. And when I say building, I mean the Amoco building in Chicago or similar. They can't use Corian® to begin with and they don't use Caesarstone® for buildings either.

So, that section of our industry is still totally natural stone, which also applies to the monument industry and the masonry industry such as BBQ’s, crazy paving paths, backyard patios, etc. So, if you say that 75% of our industry is still stone, that’s probably close.