Silicosis

The Dust Hasn't Settled Yet

Previous page: White silica sand / shutterstock

By K. Schipper

In early 2020, government reports and a National Public Radio in-depth report focused on a looming health crisis. No, not COVID-19 … the problem was increased awareness of silicosis among hard-surface fabricators, with an emphasis on engineered stone / quartz surfaces. Since then, COVID hasn’t gone away. Neither has silicosis. The basic tactic to combating airborne particles of crystalline silica – wet fabrication – seems simple enough, but years of cumulative damage to worker lungs remains. That’s become a hot issue in Australia, where banning quartz-surface importation is becoming less of a talking point and more of a possible government action. Not everyone is yet on board in the fight against silicosis, but the number of resources that can provide education on silicosis and how to combat it, is out there and growing.

WORLDWIDE ISSUE Data from studies around the world continue to paint a concerning picture of what’s happening in the lungs of many stone fabricators due to crystalline silica. When inhaled, it can reach the lower areas of the lungs, where the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide takes place. The immediate result is an inflammatory process that can, over time, lead to chronic silicosis or progressive massive fibrosis. There’s also a well-proven association between silica exposure and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis. Respirable crystalline silica isn’t just present in stone quarrying and fabrication. It also has appeared in the construction and metallurgy industries, coal and metal mining, and the manufacturing of other building materials, including bricks, concrete, glass, and ceramics. What sets the stone fabrication industry apart is the arrival and popularity of engineered stone (also known as artificial stone or natural quartz) in the marketplace. In engineered stone, the crystalline silica content can be 90% or more, compared with 5% to 30% in marble and up to 45% percent in granite. One of the most-comprehensive looks to date at the topic appeared in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, and curated research done in Italy and published in February 2019. Some of the first information on the topic came from Israel between 1997-2010, where several patients worked with engineered-stone material for up to 22 years. Over the next two years, 15 cases were diagnosed. Numbers from Spain and Italy were much the same. Forty-six workers in the Cadiz Province employed in the manufacture and installation of kitchen countertops were diagnosed in silicosis. Many of them worked in small family shops. An Italian study found 19 cases of silicosis in the region of Valencia in Spain diagnosed between 2009-2016. Since the only life-saving option in end-stage silicosis is a lung transplant, it’s a disease not to be taken lightly. The good news is post-transplant survival rates for silicosis patients and others are comparable. The bad news: those suffering from silicosis are on average eight years younger than the average lung transplant patient.

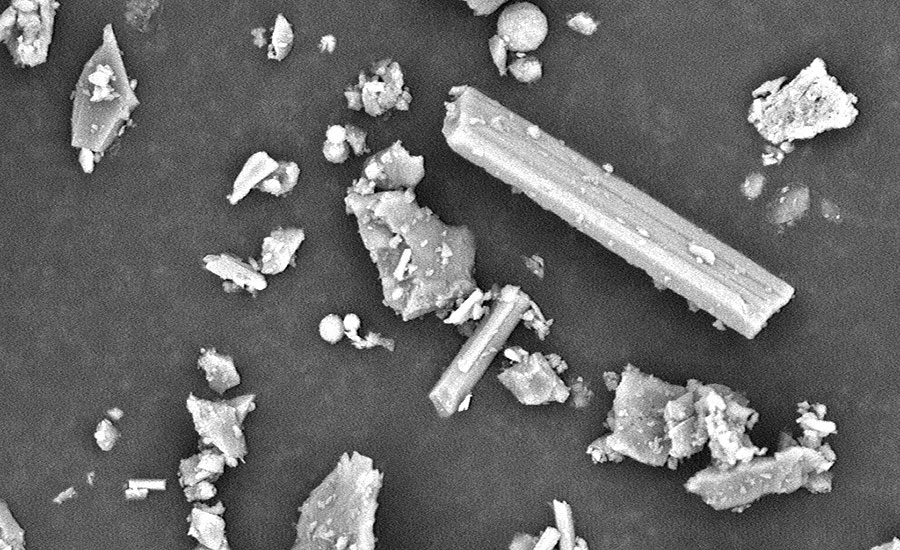

Microscopic image of crystaline particles found in silica dust. (Photo courtesy NIOSH)

UGLY PICTURE An early U.S. study on silicosis was published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Sept. 27, 2019, with cases in California, Colorado, Texas, and Washington. In both Colorado and Texas, officials noticed increases in occupational lung diseases. In both California and Washington, the study cites specific examples of people working in fabricating countertops -- mainly engineered stone. In one California case, a 37-year-old man had fabricated countertops for nine years before dying of silicosis at age 38. In Washington, a similarly aged man was referred for a lung transplant after being diagnosed with silicosis through a lung biopsy. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) earlier this year released the 2020 Annual Report Tracking Silicosis and Other Work-Related Lung Diseases in Michigan. It reports more than 1,200 silicosis cases have been identified in that state since 1985, although hospitalizations decreased in 2019 and 2020. While the state averages 20 new cases a year, estimates from 2020 are that for every case reported, another six are not. Interestingly, the disease is more severe in non-smokers, possibly because they are less symptomatic longer, and consequently the disease is more advanced when they’re diagnosed. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sets a permissible exposure limit – PEL -- for respirable crystalline silica at 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air averaged over an eight-hour workday. In the Michigan study, a sampling of 66 locations showed 40 shops above the recommended standard. OSHA also requires employers offer medical exams to highly exposed workers. In Michigan, medical surveillance was low, with 29 sites performing no medical surveillance. NIOSH started funding pilot surveillance programs in a limited number of states in the 1970s. The agency recognizes the key importance of state health approaches to addressing occupational health problems. The program’s current funding cycle includes 22 awards funded from 2021-2026. Fairly typical is the Occupational Respiratory Disease Surveillance done by the California Department of Public Health and Cal-OSHA. The program is designed to identify, characterize, and prevent occupational respiratory disease with an emphasis on work-related asthma and silicosis. Although the project mentions several industries, it specifically calls out “silica exposures and disease outcomes in the engineered-stone countertop fabrication industry.” One problem in the United States is that silicosis data are slow to be collected. NIOSH, for instance, posts information on its Work-Related Lung Disease Surveillance System to eWoRLD (www.cdc.gov/eworld), but the latest information is only through 2017. NIOSH also assessed the prevalence of silicosis in the country using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that looked at those 65 and older, but information runs from 2007-2014.

A lung with silicosis and progressive massive fibrosis. (Photo courtesy NIOSH)

DUST STORM DOWN UNDER One country that’s on the forefront of silicosis prevention is Australia. After suffering from an epidemic of deaths from asbestos exposure in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, the country jumped on the problem when doctors begin seeing cases of silicosis in 2011. In October of last year, Safe Work Australia (SWA) (that country’s version of OSHA) published a code of practice for managing the risks of respirable crystalline silica from engineered stone in the workplace, including practical guidance on how to achieve its standards of work health and safety. Responsibility for worker safety in Australia begins with the person conducting the business, but it extends to manufacturers, importers, suppliers, and designers, as well as workers and other persons in the workplace. t also stresses that workers need to be trained and given the opportunity to carry out the work safely. That means using local exhaust ventilation, water suppression, safe workshop layout, as well as the use of both PPE and RPE (respiratory protective equipment). Dry cutting should be eliminated, and alterations should not be done on the jobsite. Shop owners should also do air monitoring, and after a baseline is established, it should be repeated at least every 12 months, or when changes are made in equipment or work practices. And a baseline exam should be done before new employees start work. After the National Dust Disease Taskforce released interim guidance on silicosis in early 2020, it followed up with a period of public comments from a broad range of stakeholders, from shop owners to occupational hygienists, radiologists and people affected by silicosis, before making a final report to the Minister of Health and Aged Care. That report suggests one-in-four engineered stone workers who had been in the industry before 2018 are suffering from silicosis or silica-dust-related diseases. The situation is seen as so dire that if the recommended measures don’t achieve expected significant improvements by July 2024, then action must be taken to ban the importation of engineered stone to Australia. Shop owners responding to the interim guidance were not enthused. Stone fabrication in Australia is mostly a small-shop industry, with 75% of shops employing five or fewer people. Size alone makes it doubtful that all businesses have a good understanding of the risks associated with engineered stone. Other responses led the taskforce to feel that implementation of control measures was not being seen as mandatory and requirements were considered impractical, especially among smaller businesses, when compliance is at odds with business efficiency and profit, not to mention inconvenient. Many stakeholders also advised that the cost of compliance with any health monitoring program can be onerous for small to medium operations, while employees expressed fear of complaining because they “don’t want to be seen as weak.”

A MATTER OF EDUCATION While OSHA is certainly a part of the silicosis story in this country, the industry itself is also trying to steer people in the right direction through education. The federal agency and both the Natural Stone Institute and Caesarstone have plenty of knowledge available and readily shared with those interested. Since OSHA issued its directive “Inspection Procedures for the Respirable Crystalline Silica Standards” on June 25, 2020, the agency has issued 295 general industry citations to employers among the Cut Stone and Stone Product Manufacturing classification (NAICS Code 327991). Kimberly Darby, with the U.S. Department of Labor, says most of those citations were for failure to have an exposure assessment, no written exposure control plan, exceeding the permissible exposure limit and failing to meet medical surveillance requirements. Trailing behind were write-ups for actual lack of respiratory protection. For how to avoid these issues, Darby recommends OSHA’s crystalline silica webpage at www.osha.gov/silica-crystalline, which includes information on the health effects of exposure to silica and on how to comply with the agency’s silica standards. Mark Meriaux, the Natural Stone Institute’s accreditation and technical manager, says he hopes business owners are using its resources, specifically those at www.naturalstoneinstitute.org/silica which are free to members and nonmembers alike. He also recommends new training videos put out by the Georgia Institute of Technology department of Safety, Health, Environmental Services (SHES). “The biggest notable difference in this OSHA training versus guidance from the Natural Stone Institute is the primary methods of compliance,” Meriaux says. “OSHA guidance strongly recommends the use of PPE (personal protection equipment) as the main method to control exposure. “NSI guidance recommends other methods, such as wet processing, housekeeping practices and HEPA air filtration as primary steps to reduce exposure below OSHA-defined action levels, with PPE as a final option when exposure levels can’t be met using these other methods.” Another option for learning more about silicosis and how to prevent it is through Caesarstone and its Master of Stone training program. Yael Goldshmid, director of Brand Marketing, America for the company, calls the program (available at mos.caesarstoneus.com/) a great success and people who have taken it say it has definitely enhanced their knowledge on a number of safety topics. Made up of some 30 modules, it covers everything from common practices to procedures for a safe work environment and health hazards related to silicosis. Goldshmid adds that more modules will be added as Caesarstone brings its porcelain product to market. “That has different risks and different needs that should be addressed,” she says. “As we grow our company to be multi-material, we’re taking that into consideration with our Master of Stone program.” Regardless of what shop owners do to learn about the dangers of crystalline silica, Meriaux says the bottom line is their shops need to be tested to gain a better understanding of where additional safety controls and efforts should be focused. Shops also need to implement engineering controls and/or PPE to reduce worker exposure to within mandated levels; and create a silica exposure control plan that includes both training and recordkeeping. If there’s a bit of good news in all this, Meriaux notes that while the number of citations from OSHA is up this year, penalty fines are down. “I hope this means more shops may be in violation, but overall risk and seriousness of the hazard is down,” he observes. “I believe that the industry has improved methods with many shops going to exclusively wet process, but unfortunately I still visit some where they employ some dry processes.”◘